Marcantoniana

Items from the Life and Times of the Marvelous Vito Marcantonio.

Sunday, April 7, 2024

"Marcantoniana" to Book Form

Wednesday, August 16, 2023

Birthday Card for Tina Modotti

Pure your gentle name, pure your fragile life,

bees, shadows, fire, snow, silence and foam,

combined with steel and wire and

pollen to make up your firm

and delicate being.

--Pablo Neruda

Today is Tina Modotti's birthday.

She would have been 127, but during her short 46 years, Modotti lived a century's-worth.

"Marcantoniana" admires Modotti, not just for an unparalleled commitment to working people, but for the rich texture she wove into her existence, and a willingness to embrace not just what came her way, but the trouble she looked for and found.

By way of birthday card for the fabulous lady, we will sketch a resume of her brief, but full-fledged, engagement with the World.

Modotti was born in Udine, Italy. Her real, first name was Assunta. Poppa was a craftsman who followed the currents of work through the western factory world, so that she spent some years in Austria before taking off, as a teen, for San Francisco.

There she worked as a seamstress in factories while Momma fed her pasta and Poppa the rantings and songs of the anarchist-inspired International Workers of the World -- the Wobblies.

Modotti liked the theater and, at some point during her development into a first-class vixen, was tapped by a Hollywood talent scout to go south and settle in Los Angeles.

There she played the exotic and foreign siren in a number of A-list productions such as "The Tiger's Coat" and "I Can Explain."

Tina married and fell in with a bohemian crowd that counted among its numbers Edward Weston, a still-renowned photography pioneer at whose knee she learned the craft, while simultaneously having an affair with him.

She was, by any measure, a seductress with a healthy sexual appetite.

Her husband tempted Tina into visiting post-revolutionary Mexico. Weston followed. There she stayed and delved into that wonderful and beleaguered nation's cornucopia of colors, sounds and flavors, honing her craft into a portfolio much-admired even today.

Modotti mixed with muralist Diego River and his wife (not Frida, the first one), Siqueiros and other figures of the Mexican left until her commitment grew enough to join the communists' feeble efforts to overthrow an already corrupt regime.

When her first husband died Modotti became lover to a Cuban Marxist named Julio Mella, who was shot as he walked with her down a Mexico City street. She was accused as an accomplice in the murder.

Surviving the legal i

nquest, she nonetheless acquired the sobriquet, "The Bloody Tina Modotti."

nquest, she nonetheless acquired the sobriquet, "The Bloody Tina Modotti."Sooner than later, the revolution melded seamlessly with her own life. After somebody tried to kill the Mexican president, Modotti was tossed from the country and into a wanderer's existence served exclusively on behalf of the worker's cause.

Her art was dedicated to the same cause, but unlike socialist realism and other products of the era, Modotti never took up a cudgel. There is nothing bombastic or cloyingly heroic about her photographic subjects.

Rather than impose a communistic view onto the world, Modotti found natural instances, bits of workerist filigree that she highlighted with a Graphlex lens and whatever light was at her disposal.

The compositions are often exquisite.

Berlin, Austria, Paris...Modotti served as a spy in the service of the communist movement. Like many well-meaning progressives, she wasted her countless and life-threatening efforts on the schemes of wicked Joe Stalin.

Few knew what Stalin was until it was too late, that's what is said. Still, it was not necessary, this falling into the trap of losing God only to replace him with the leader of Russia's Communist Party, good or bad.

But we all make mistakes. The swoop and sweep of our lives can be ennobled by their smaller embellishments.

Modotti was dispatched to Spain along with her lover Ennea Sormenti, where she worked as a nurse for the international communist medical auxiliary, staying until the Spanish Republic's tragic demise, squiring beleaguered refugees across the icy Pyrenees mountains in the winter of 1939.

Tina floated the world over on a barge for a while, no country willing to take her in. Mexico finally relented. She died there in a cab a few years later, her life only partially rebuilt.

Elena Poniatowska, Mexican author of the definitive biography, "Tinisima," crafted a quiet expiration brought on by a life of high-drama and chain-smoking.

Others speculate her life on the political and romantic frontlines might have spurred someone to murder La Modotti.

Either way, the mystery befits a woman who led an uncommon existence, following her bliss, seeking a higher purpose, molding life itself into a work of art.

Saturday, July 8, 2023

Book Report: "Down These Mean Streeets" by Piri Thomas

"Down These Mean Streets"

The first book is true to its title: a young man's coming of age along the dangerous byways of Spanish Harlem.

Here we see the perils associated with traversing the concrete jungle, the need for toughness and concomitant death of tenderness in youth.

Author Piri Thomas details what life was like for Puerto Ricans moving into what had been an Italian neighborhood and the Italians' response to their displacement.

Thomas was born in the 1920s, so that the time covered here ranges from the '30s to, perhaps, the early '50s, rendering his once hip track of new-lit jargon and streetjabber something of a timepiece.

Thomas' novel came out in 1967 and one can imagine the liberal chic set of Mayor John Lindsay's New York jumping like cats to nip at his rough-edged peek beneath the shiny Big Apple's skin.

Although this kind of literature has become stock in the book trade (James Frey anyone?), Thomas' autobiographical recounting of life among the rough Puerto Rican boys on his street can still shock.

His detached description of when the bored kids willingly go up to the apartment of some transvestites for homosexual interaction, pot, and booze, is rather striking and unsettling.

The second "book" deals with young Piri's identity crisis. One which can be extended to all the Puerto Ricans of his time.

highwayscribery is ignorant of what they are thinking today, but in Thomas's time, there was much ado over skin color, the islanders running from evening black to lily white as they do.

Thomas' problem was that he was darker, while his brothers were white. As a Puerto Rican, he did not, at first, view himself as being in the same boat as the African-Americans with whom his people crowded Harlem.

But when the family makes an escape to suburban Long Island, Piri comes in for a bit of a shock, and slinks back to "El Barrio" with a severe chip on his shoulder and a deeper sense of shared experience with the American Negro.

This issue is aired-out in discussions with folks of different skin pigmentation, each of whom expresses a unique understanding of the related questions. For this reviewer, it went on a little too long, and seemed a little self-indulgent.

Especially for a young man confronted with the serious matter of economic survival in a cruel and unforgiving city.

Nonetheless, Thomas' youthful obsession generates an anger which serves as bridge to the third book, which is a jail tale.

Identity issues unresolved, his skin color serving him poorly in prejudiced city, the young man goes on a crime spree, again remarkable for its matter-of-fact execution, which lands him in the state penitentiary.

Perhaps it was novel at the time, but today his efforts to maintain a tough guy's rep -- primarily to avoid being sodomized by bigger, harder criminals (no pun intended) -- while rehabilitating himself with a little Nation of Islam cant and some in-house masonry training are now familiar fodder.

Thomas' attempt to forge a street-seasoned prose is uneven. He never really finds a groove and seems almost relieved to let more articulate characters do some of the heavy lifting where the expression of complex ideas is involved.

Nonetheless, he succeeds in engaging the reader, pulling of that time-tested trick of getting people to root for a guy doing bad things, by peeling back the hard layers and revealing a human and worthy heart.

Friday, February 10, 2023

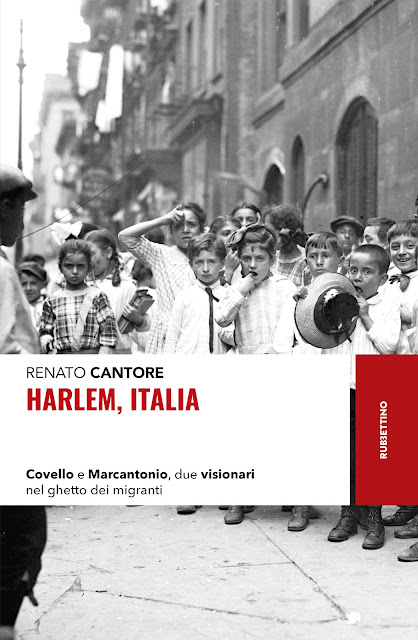

Two Italian American Lions Reborn with Renato Cantore’s “Harlem, Italia”

Vito Marcantonio and Leonard Covello Reconsidered in Italian-Language Publication

Italian Harlem, and

its two main

prominenti, Leonard

Covello and Vito

Marcantonio, have

been brought to

literary life in

Renato Cantore.

Cantore, deputy director of Rai-Tgr, Italy's television network for regional news, has published numerous books and articles on the history of Italian emigration to the United States. “Harlem, Italia,” published by Rubbetino, is an Italian-language effort intended to educate people on immigration and its history.

“Italians are getting to know the immigration problem,” said Cantore in a Feb. 10 interview. “I think knowing the history of when we were immigrants can be very useful for all of us.”

Leonard Covello was an educator in East Harlem, a veritable pillar of the community, who worked to gain respect for his people and their language. Marcantonio was a student of his who went on to become a congressman and important collaborator to Covello where the construction of Benjamin Franklin High School - and other community-based efforts - were at stake.

It has been a while since there was a big book written in this academic space. Allen Schaffer’s “Vito Marcantonio: Radical in Congress,” was published in 1966. Salvatore LaGumina’s “Vito Marcantonio: The People’s Politician,” came out in 1969. Gerald Meyer’s “Vito Marcantonio: Radical Politician” was published in 1989.

Covello’s own “The Heart is a Teacher,” was released in 1958. “Leonard Covello and the Making of Benjamin Franklin High School: Education as if Citizenship Mattered (Michael Johanek and John Puckett) is the most recent effort with a 2006 publishing date.

So, Cantore’s fresh scholarship is both needed and welcome.

In “Harlem, Italia,” he revisits the largest Little Italy in the U.S. - East Harlem - during the first half of the 20th century, with a specific focus on Covello and Marcantonio. The former was a sociologist, educator and community activist, the latter, a famous radical congressman of the American Labor Party.

Said Cantore: “Despite having the possibility, they never left their troubled neighborhood behind for fancier parts of New York City. They lived all their lives in East Harlem. This is where their friendship started, and it is here where they started a project that did not merely revolve around themselves, but around the community in general.

|

| Renato Cantore |

“Both became leaders in their respective fields, but never ceased to work for the East Harlem community’s emancipation.

Italian Americans, he noted, were an "unwelcome" people but grew, by the 1930s, into the largest ethnic community in East Harlem; figuring prominently in the political and social life of the neighborhood.

“My book,” said Cantore, “recounts that neighborhood life through significant events: the construction of the Madonna del Carmine Church on 115th Street; the activities of Harlem House; Covello's struggle to have the Italian language taught in New York's schools; LaGuardia and Marcantonio shaking up Gotham politics; the idea of a multi-ethnic society based on mutual respect and collaboration; the pedagogical project behind the Benjamin Franklin High School - the first high school in East Harlem - where Covello reigned as principal for 22 years; the realization of a massive, social housing program for thousands; civil rights campaigns; Marcantonio's electoral campaigns, and his radical ideas in opposition to consolidated powers.”

Cantore first encountered Marcantonio and Covello while studying Italian emigration. He had the good fortune of meeting with the preeminent Marcantonio scholar of the day, Gerald Meyer who argued that the importance of these two “giants” should be better known in their country of origin.

“Meyer shared books, documents, memories and encouraged me to continue my research,” explained Cantore. Gerald Meyer died in November 2021.

Cantore also studied LaGumina, Schaffer, Christopher Bell (“East Harlem Remembered” etc.), Robert Orsi (“The Madonna of 115th Street” etc.), and Italian cultural scholar Simone Cinotto (“The Italian American Table: Food, Family and Community in New York City” etc.) in constructing his story.

“I read the newspapers of the time, consulted documents, met a lot of seniors from East Harlem, and also followed the activities of the Vito Marcantonio Forum and the blog “Marcantoniana,” said Cantore.

The book, he stated, is aimed primarily at young people; school and university students, but also adults; especially those involved in education and politics. “They will be interested in knowing the story of Leo and Marc, and their long walk towards the integration of the Italian community of Harlem,” he predicted.

Cantore is maintaining a brisk schedule of public appearances with key events in Picerno, where Marcantonio has his roots, in Avigliano, so well-depicted in Covello’s aforementioned memoir, and other municipalities in the province of Basilicata, where the story is truly rooted.

“We are preparing a vast program of presentations in other Italian regions, literary fairs and colleges,” explained Cantore.

“In the end,” Cantore said, “I hope that this book will render a tribute of gratitude to Covello and Marcantonio, in Italy, for what they have done. Their example is relevant, useful, and applicable to the times in which we live. We need a renewed commitment to the poor, the needy, the immigrants who remain on the margins of the community, just as it happened for the Italian-Americans of East Harlem.”

The Goodfather: A Novel by Stephen Siciliano

Wednesday, June 9, 2021

Gil Fagiani in "Italian American Review"

Introduction to a series of remembrances about poet and Vito Marcantonio Forum co-founder Gil Fagiani, for the current edition of “Italian American Review,” which is created by the City University of New York’s Calandra Italian American Institute and published by University of Illinois Press:

Gil Fagiani: Objectively Speaking

The French existentialist philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre asserted two modes of being: consciousness (pour-soi) and object (en-soi). The former, Sartre asserted, requires the latter; consciousness exists only in its relation to the objective world.

Consciousness implies the objective world and its own existence as a question.

The questions Gil Fagiani asked, in an effort to know himself and give his existence meaning, can be sought in the ample and elevated body of work he left behind, as writer and poet, upon passing on April 12, 2018.

Provincial Italy, New Left politics, addiction, redemption, romance, Latin-spiced urban streetscapes, are rendered in flavors only realizable in a man striving to understand the relationship between his consciousness and the objective world, a dialectic Sartre considered the foundation of knowledge and action.

In this collection of remembrances, we make contact with Fagiani’s en-soi, his consciousness as it existed to those around him -- remembrances confirming Sartre’s contention that “there can be no free pour-soi save as engagement in a resistant world.”

For engaged the poet and activist was.

Here we have Fagiani’s lifelong friend, Genie Bild, recalling New York City’s anarchic 1970s, when the pair worked with the activist group White Lightning. Professor Gerald Meyer reviews a thirty-year friendship and collaboration rooted in recuperating the memory of radical Italian American Congressman Vito Marcantonio. Roger Harris harkens back to Manhattan’s riotous ‘60s and his work with Fagiani and the East Harlem Tenants Council, remarking on his comrade’s fateful link to the neighborhood. James Tracy’s research on a book brought Fagiani into his life, and in time he came to know “the multitudes within him.”

For Sartre, death was not annihilation but the lapse of one’s subjectivity out of the world. The meanings we leave behind are modified at the hands of others. Our consciousness exists, finally and solely, in the minds of those who perceive and remember us.

In these writings of four men who can claim to have known him well, Gil Fagiani is not annihilated; rather, he exists and changes and endures.

----Stephen Siciliano

Volume II, Number I of “Italian American Review” can be purchased here:

https://www.press.uillinois.edu/journals/iar.html. or from Clydette at cwantlan@uillinois.edu

"The Goodfather (A Novel): The Rising Fall of the Marvelous Marcantonio" can be found here: Marc Lives

Saturday, May 1, 2021

Christopher Bell's East Harlem

A recent article on the website “Harlem Focus” details how the “real” Little Italy was not actually on the lower East Side, but uptown in East Harlem.

An interesting report, it contains nothing that can’t be found in Christopher Bell’s “East Harlem Remembered,” which is not to criticize, rather to illustrate the need for the retelling of stories to keep them alive.

As such, we reconsider Bell’s work, which was published in 2013 ...to retell it, and review it in light of the time which has passed since and, perhaps, to mine it for further value.

Of particular interest to this website is Bell’s inclusion of a stand-alone, chapter-length, mini-bio of Vito Marcantonio, establishing him as the emblematic East Harlemite “non pareil” in spite of a local constellation that includes folks like Burt Lancaster, Langston Hughes, or the most-contemporary Marc Antony.

While addressed directly in said chapter, Marcantonio’s imprint upon East Harlem’s neighborhoods can be perceived throughout the book in passages where he is not mentioned by name.

Resident Felipe Luciano noted how in the 1960s and ‘70s the Young Lords Party had a group that, “simply advocated for people who need help to pay a ConEd Bill, or if they needed translation with the Welfare Departments or if you needed help with the homework.”

Such were the needs of Marcantonio’s constituents and the way in which he handled them became the blueprint for those who took up the tasks in the wake of his sudden departure.

Bell noted that, after World War II, the city’s housing and planning entities failed to engage neighborhood agents, “unlike before when Leonard Covello and the East Harlem community worked with Vito Marcantonio and Mayor Fiorello La Guardia to bring the East River Houses to the neighborhood.”

Which is a reminder that a locale doesn’t necessarily recycle good leaders in succeeding generations and that their presence is a matter of good fortune, their death, the opposite.

A noteworthy achievement is the voice, the bullhorn even, “Remembered” gives to the residents of East Harlem.

The Written Words

A cursory review of East Harlem literature brings to mind Patricia Cayo Sexton’s “Spanish Harlem: Anatomy of Poverty,” which contains testimonials from the neighborhood, but is an academic document that provides the uninitiated with an institutional and demographic topography of the area, moreso than the soul of a people.

Poet Gil Fagiani’s “A Blanquito In El Barrio,” is rich in local idioms both visual and verbal, but the work is primarily in one voice, the poet’s -- with its shadow of the suburban Connecticut youth -- observing East Harlem as much as living it. Though Fagiani’s life was linked to the place in fateful ways, “Blanquito” is the voice of an eternal visitor delighting in exotic urban fauna.

Piri Thomas’s “Down These Mean Streets,” harnesses the power of literature to enmesh readers in a gritty personal drama with East Harlem as the backdrop, but it is a largely personal journey and, as with Cayo Sexton’s work, features portraits drawn primarily from the Puerto Rican community.

Michael Parenti’s “Waiting for Yesterday:Pages from a Street Kid’s Life” is a remembrance of the old haunts and characters via a singular voice--Parenti’s.

Bell’s book is, still more, a lively pastiche of vox populi, the purest presentation of East Harlem in its own words. Rife with colorful, colloquial recollections presented “as-is,” and homemade snapshots, “Remembered” hums with authenticity.

These people were there and Bell was able to land some big fish such as author Thomas, and Raoul Abdul, a confidante of the poet Hughes, but these have nothing over the rank and file residents he rounded up for recollection.

Here is Piri Thomas describing Marcantonio: “I thought he was Puerto Rican because he helped everybody, all nationalities. The Puerto Ricans and Italians were always fighting and he was helping everybody out.”

Joe Monserrat remembered how Marcantonio’s mentor Leonard Covello, “believed Italians should have rights, and African Americans and Puerto Ricans should have rights too. Despite the tension and fights between the groups, Pop Covello was one of the first to recognize Puerto Ricans in the school [ Benjamin Franklin High School] and in the community. The school was a community center and it was a very nice place.”

The Grassroots Perspective

These are examples of how East Harlemites actually viewed such community leaders; not through a prism of left and right, or career arcs to be analyzed, but through neighborhood, political interaction and personal contact.

With statements such as these we learn as much about Marcantonio as we do from an analysis of his legislative record or adherence to a particular party line.

In the following statement from Hortencio Morales, we learn of unique skills the city kid picked up during an apprenticeship on the streets:

“You had the fire hydrant, or the water pump, which we called la pumpa. The water pump was always open on every block in East Harlem. Someone in the neighborhood would get this big wrench to turn the water on. Next you found an empty can and scraped both sides of the can until both lids came off. With the water coming out of the hydrant at full blast, you placed the can in front of the nozzle and you had a powerful force of water gushing out.

Now that’s an East Harlem story.

Parenti’s remembrance marveled at the adaptability of street kids to their environment. Willie Lopez fills in the details, brings that spontaneous creativity to life.

Lopez recalled how stickball was: “...played on every block….You pitched or bounced the ball once on the street and you have one swing. The batter runs into the ball and, hopefully, you hit a hard line drive down the street. If you hit it on the roof, that’s an out, but when you played on the block, you always had fire escapes. Your goal was to hit the fire escapes or the wall because, if it bounced down off the wall, that’s how you could get an extra run.”

A Disappeared World

The assembled oral accounts, a few of which harken back to the late 19th century, recall forgotten features of quotidian life, provide a description of James Bryants’ iceman [maybe it was Michael Parenti’s father], the icebox and its operation, an explanation of the prevalent use of dumbwaiters in tenement buildings.

Bell gets into the weeds with the formation and history of local institutions, but this detail aids in spinning the web of relationships that make neighborhood a community; the wispy thread tying LuLu’s Candy Store to Joe Cuba’s vibraphone player. No group is slighted where their history and contributions are concerned. Bell even dug out a member of the small Greek community nestled among all the Italians, Jews, Puerto Ricans and African Americans.

Bell gets into the weeds with the formation and history of local institutions, but this detail aids in spinning the web of relationships that make neighborhood a community; the wispy thread tying LuLu’s Candy Store to Joe Cuba’s vibraphone player. No group is slighted where their history and contributions are concerned. Bell even dug out a member of the small Greek community nestled among all the Italians, Jews, Puerto Ricans and African Americans.

None of the accounts deny the area’s poverty, but neither do they dwell on it. For all its poverty and crime, people looked back fondly upon pre-redevelopment East Harlem as a collection of neighborhoods with what Robert Stern, another of Bell’s subjects, called a “dense network of associations.”

Said Morton Ross: “When I was a kid we threw away the key because we didn’t lock our doors in East Harlem. It was a “whose a dare?” system and anyone came in the building there was a superintendent or a janitor. And if someone came by your building that didn’t belong there, or if a person banged on the door, our Italian janitor said “whose a dare” and that trespasser ran like hell.”

Carlos De Jesus recalled an “open community” of fluid exchange and relation between residents.

Bell, for his part, provides naught but the unvarnished truths where East Harlem’s afflictions are concerned, but even in an accounting of street-gang presence, something of an ebullient urban lexicon surfaces:

“There were gangs all over the place. On 102nd Street the gang was called the Demons; 103rd Street gangs were the Dragons, and also the Copian (Copasetics) patrolled that area. No gangs existed on 104th Street until we started our gang, the Condemners. The Viceroys’ turf was on 110th Street and sometimes they came to 103rd Street to fight the Dragons on 105th Street was the Corsicans territory and on 106th the Colts ran that area.” [Manny Segarra]

The Public Housing Phantom

Bell tarries long on the identity imposed upon East Harlem via public housing policies decided beyond its confines; the immutable reality that transformed the area and erased its past save for voices like those archived here.

“Remembered” is a guided tour through both the time and space that has been, and is, East Harlem, an excursion through successive East Harlems. Bell even applies a tour guide’s language, opening up one chapter: “Here we will read how one man’s vision...”

The author, while constructing a fair balance sheet on redevelopment’s record in East Harlem, is not afraid to render judgement, calling it, “The tenement carnage and relocation.”

Arnie Segarra, resident of the Johnson Houses on Lexington Avenue, put things within the context of the times: “Housing projects were luxury housing back then and it was the first time anyone rode in an elevator and had a maintenance crew.”

Manny Segarra summoned the scars redevelopment left behind both on the landscape and individual psyches. ”Scores of tenements were destroyed, which left empty lots and this practice was commonplace throughout the city. I was ten years old and I kept thinking that everything would be OK. But I went downstairs and saw the empty buildings."

Bell maintains a loose, progressively tinted narrative history of the United States throughout the arc of East Harlem’s tale, always tying what was happening in the neighborhoods to larger societal trends, while highlighting a community asserting its own relevance beyond the East River.

Vito Marcantonio Forum Kicks Off Rebel Girl Series with "Elizabeth Gurley Flynn: Why Now?"

The zoom event represented a first collaboration between the Vito Marcantonio Forum and Claudia Jones School for Political Education; “two educational and cultural political organizations sharing a vision that history matters,” said moderator Maria Lisella.

Reissued by International Publishers', “My Life as a Political Prisoner. The Rebel Girl Becomes No.11710,” was first published as “The Alderson Story.”

Trasciatti, who is a professor of writing studies and rhetoric at Hofstra University, and president of Remember the Triangle Coalition,is currently writing a book on Flynn for Rutgers University Press.

She also contributed the forward to the new edition of Flynn’s prison memoir, which came out in 1963, one year before its author died. “Her experiences at the penitentiary for women is what the book is about,” Trasciatti told the online audience.

The professor began with a discussion of Flynn's life and work. Born in 1890, her parents were socialists and fighters for Irish freedom who moved in a radical milieu, which led to her youthful entry into the world of political activism.

“The material conditions of her poverty and struggle, as well as the ideological education she received from her family and her friends,” Trasciatti observed, “were the foundations for Flynn’s deep understanding of the inequalities that pervaded U.S. society and politics and of her broad international vision.”

The professor spoke of a life divided in two parts; the first being “The Rebel Girl,” when Flynn adhered to syndicalist principles and direct action, rather than electoral politics.

At 16, Flynn signed on with the Industrial Workers of the World union -- the Wobblies -- described by Trasciatti as, “an exciting and audacious group at the heart of some of the most important industrial labor actions of the early 20th century.”

Flynn led free speech fights that shaped the IWW’s future campaigns on the issue. She played important roles in the Lawrence, Mass., “Bread and Roses” strike, the Patterson, N.J. silk strike, New York hotel workers job action, and the iron workers walkout on Minnesota’s Mesabi Range.

She was arrested for being a member of the Wobblies when she had left the union and escaped imprisonment by petitioning President Woodrow Wilson; an experience which spurred her founding of the Workers Defense Union to help in similar cases, and which often represented the only legal representation such defendants could find.

The Rebel Girl’s unique talent was bringing a fractious left to the table with the liberal establishment. “She was instrumental in forging the liberal-radical alliance historians note was at the heart of the post-war civil liberties movement in the United States,” Trasciatti asserted.

Flynn fought deportations and called, throughout her life, for political prisoner status in the U.S., where it does not exist. “Hence the title of her book, ‘My Life as a Political Prisoner,’” Trasciatti explained.

In 1920, Flynn helped found the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) with which she worked for 20 years, before the association came to an end over her membership in the Communist Party of the U.S.A. (CP).

In 1926, she suffered a breakdown when upon learning that her lover, the anarchist Carlo Tresca, had been romancing her younger sister and produced a child in the process. It was the last straw for a spirit exhausted from incessant advocating, agitating and traveling, according to Trasciatti.

This precipitated a move to Portland, Oregon, where she lived quietly for 10 years with a friend before entering the second half of her career as a member of the Communist Party from 1947 to 1964.

“These are the years when Flynn is no longer a girl, but still a rebel,” said Trasciatti.

In 1961, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn was elected to a three-year term as the CP’s first female chair. The fit between Flynn and the party was a natural one. In 1937, the CP was the most active, inclusive and exciting organization on the left, according to Trasciatti, who added, “She wanted to be in the fray.”

It helped that Flynn’s joining coincided with the Popular Front period during which coalition-building skills were at a premium. An anti-fascist going back to the 1920s, Flynn liked the CP’s dedication to that fight.

|

| Professor Trasciatti |

During the turbulence, anti-communists in the ACLU sought to dissociate the group from the Communist Party; to shed its radical past and embrace a politically neutral version of free speech, which many have applauded, but which Trasciatti characterized as “a problematic moment in the history" of the outfit.

In Feb. 1940, the organization passed a “Commu-Nazi” resolution, asserting the two ideologies represented one side of the same seditious coin. Neither political animal could sit on the ACLU board, because these credos undermined their commitment to civil liberties.

Flynn, the only communist on the ACLU governing body, was asked to step down, but refused; instead challenging the directors to both try and purge her, which they obliged in May 1940.

“Ponder the irony,” Trasciatti observed. “Elizabeth Gurley Flynn had been an anti-fascist since 1923, before anybody else on the ACLU executive committee, and now the ACLU was telling her that her political ideas were as dangerous as fascism. That cut deep.”

Her ouster, Trasciatti said, gave a liberal seal of approval to anti-communism and set the stage for everything that followed in its name.

In 1976, the ACLU expressed its organizational regrets over the move.

Also in 1940, Congress passed the Alien Registration Act; the first peace-time, anti-sedition law enacted since the Alien and Sedition Act of 1789.

Known as the Smith Act, the bill made it a crime to undermine the morale of the U.S. military or advocate overthrow of the government by violence, and required the registration and fingerprinting of all adults, noncitizen residents.

“The path towards internment,” observed Trasciatti.

The CP opposed the law throughout its enactment as anti-immigrant, antithetical to civil liberties, and unAmerican. The party urged President Franklin Roosevelt not to sign it.

“The law proved a potent weapon against the left,” said Trasciatti.

The first significant indictments came in 1941, against 39 members of the Trotskyite Socialist Workers Party. Some defendants were Teamsters and Trasciatti cited literature suggesting the union colluded with the government to remove them from the syndicate.

The trial, “a travesty,” according to Trasciatti, was one of political ideas that set a very low bar for seditious speech and resulted in 18 defendants being sentenced to a year, or more, in prison.

The Communist Party did not work on behalf of the defendants, as they were Trotskyists, but not long after World War II, it too became a target of Smith Act prosecutions.

In 1949, 11 CP leaders were arrested, tried and convicted. Elizabeth Gurley Flynn chaired the party’s Smith Act Defense Fund to raise money and generate sympathy, but “it was a really tough sell in that political environment,” Trasciatti remarked.

In 1951, a second group was arrested, including Flynn, Jones, Betty Gannett and Marianne Baccarat.

At trial, Flynn acted as her own counsel. “She had an interest in legal affairs, but more importantly, her book makes clear how nobody wanted to defend these people,” said Trasciatti.

Flynn’s speeches in court, she continued, “offer a stirring indictment of capitalist justice and defense of the right of Americans to their own political beliefs and opinions.”

Memoirs

Nevertheless, in 1953, all of the defendants were found guilty. Flynn’s sentence was 28 months in the Alderson Penitentiary for Women, and these months yielded the book under consideration.

The title, Trasciatti noted, reflects Flynn’s longstanding commitment to civil liberties.

“She acknowledges that there are political prisoners in the U.S., that we incarcerate people for their ideas, and for the things they say, not the things they do. That recognition is part of what sustained her through imprisonment,” said Trasciatti.

Flynn acknowledged her fellow political prisoners, the professor asserted, not to call attention to the plight of communists, or other imprisoned political activists, rather to highlight the inhumanity of what passed for justice in the U.S.,as experienced by the ordinary women she found herself surrounded by, and to call for change.

“Many of the topics she addressed in the book make it feel like it could have been written yesterday,” Trasciatti observed.

These included the dehumanizing effects of incarceration, the creep of militarization into the prison system, the class composition of the jailed population, and the understanding of incarceration as a racist institution.

She railed against the exploitation of prison labor, and took the position that “addiction is a disease not a moral failure. A very forward thinking approach,” said Trasciatti.

“My Life As…" she added, presents a rare personal account of what it’s like to be a woman behind bars.

Trasciatti quoted Angela Davis who wrote in “Women Race, and Class,” “[The book] reveals a new political maturity and a more profound consciousness of racism. As a leader of the Communist Party, Elizabeth Gurley Flynn had developed a deep commitment to the black liberation struggle, and had come to realize that black peoples’ resistance is not always consciously political. At Alderson, she made friends more easily among the black women in prison than she did among the white inmates. And the black women, in turn, were more receptive to Elizabeth. Perhaps they sensed in this white woman communist an instinctive kinship in the struggle.”

Although 28 months in prison were undoubtedly hard on an older woman, Flynn left unbowed, “formidable,” said Trasciatti.

Flynn died in Moscow in 1964.

The presentation can be viewed in its entirety at https://youtu.be/3BhN9Nvh3RQ

"The Goodfather (A Novel): The Rising Fall of the Marvelous Marcantonio" can be found here: MARC LIVES